A discussion with Ziaur Rahman, Rohingya activist and humanitarian

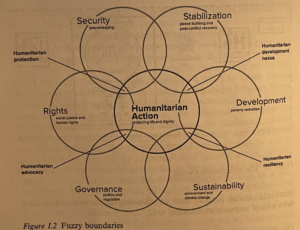

As defined by Maxwell and Gelsdorf1 humanitarian action, broadly speaking, is the protection of life and dignity. Inherently multifaceted, humanitarian action includes eight overlapping realms including security, stabilization, development, sustainability, governance, and rights. Where humanitarian action overlaps with both governance and rights lies humanitarian advocacy. They argue,

“Humanitarian action is is always situated in a context of global agendas, and it is often unclear where humanitarian action ends and some other kind of action begins–whether this action is more explicitly political, developmental, economic, or human rights oriented. This question also tugs at the very meaning of  ‘humanitarian’- and is by no means resolved.” (p.7)

‘humanitarian’- and is by no means resolved.” (p.7)

I cannot agree more, and am constantly challenged by my own shifting views on the meaning of humanitarianism. I’ll readily admit to erring on the side of conflating humanitarian work with direct humanitarian advocacy. On my journey struggling to define ‘humanitarian’ I have taken to listening to and observing the actions of those who are themselves the victims of systemic and violent marginalization and are at the same time advocating for themselves, doing whatever it takes to protect life and dignity.

See here for my series of blog posts on ‘refugee humanitarians’.

In that spirit, I below share a recent conversation with a Rohingya writer and activist exiled in Malaysia. Much has happened in Myanmar since we first talked, and I will have more to say about that soon.

Ziaur Rahman, Rohingya Activist

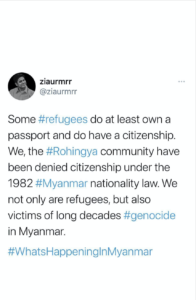

I have been honored to meet many Rohingya women and men in the last couple years as I do research on the humanitarian sector, and I have learned from each something unique and valuable. Ziaur Rahman is in the process of having his memoir published, and in this book he describes his life as a refugee, part of the Rohingya diaspora spread around the world. A refugee for 29 years and technically ‘stateless’ since Myanmar does not recognize  Rohingya citizenship, Ziaur has made Malaysia his adopted home. His official identification card is from the UNHCR and he remains in wait for the dim possibility of repatriation back to Myanmar.

Rohingya citizenship, Ziaur has made Malaysia his adopted home. His official identification card is from the UNHCR and he remains in wait for the dim possibility of repatriation back to Myanmar.

Below is our discussion.

Arcaro: Your homeland is known by two names. Which do you use and which do you prefer people like me use, Myanmar or Burma?

Ziaur: “It was changed by the country’s government from the “Union of Burma” to the “Union of Myanmar” in 1989. But Myanmar is now used world-wide so we have also need to use it.” I prefer to use Burma instead of Myanmar.

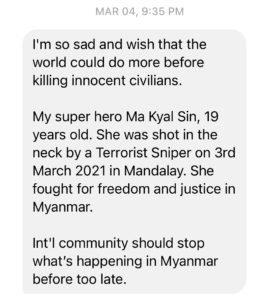

Arcaro: As a Rohingya can you tell me your reaction to what is taking place right now in Myanmar regarding the military coup and the public response to that. What are your tho ughts and feelings about the military is using lethal force?

ughts and feelings about the military is using lethal force?

Ziaur: “The Myanmar military [also known as the Tatmadaw] always creates problems for Myanmar people. It’s the longest standing military dictatorship and applied numerous sanctions against Myanmar but nothing has changed.

I can’t hope for anything good in Myanmar. The military first came for the Rohingya for persecuting and are now persecuting other ethnic

people of Myanmar.

I would be interested in knowing when the next elections will take place, and what measures are being taken to assure fair and free elections for the new elected president of Myanmar for real democracy.

The military control in Myanmar has been very dangerous for my country for decades. The military that now has power in Burma after the coup is the same military that committed genocide against the Rohingya and other Myanmar minorities in Myanmar.

My parents, including my grandparents, wanted democracy in Myanmar. That is what the protestors want. A second demand is to release Aung San Suu Kyi because she was the daughter of Aung San, a true democracy leader of Myanmar. Our grandparents and parents are still fighting for democracy in Myanmar. I am also a supporter of democracy in Myanmar like my grandparents and parents; I am showing solidarity to the people of Burma for peace, democracy and stability because we are the same product of persecution by the military.”

Arcaro: What can be done by outside communities?

Ziaur: The International community and ASEAN should strongly pressure the Myanmar military to end the coup. And give back power to the rightful elected leaders. I think it’s good that Joe Biden, President of the US, is allowing more refugees into his country. I want other countries to welcome us and to sign the 1951 Refugee Convention which allows more protection for refugees. The international community, the UN, and other powerful bodies must work for the opportunity for us to safely and with full citizenship and rights be repatriated to our country.

I would like to recommend that you and others speak out regarding this injustice and the silent genocide of my people in Myanmar.

Arcaro: Do you think that it is possible that sometime in the future you will be able to live back in Myanmar?

Ziaur: “I don’t think i can go back to my country soon. I see some possibilities as people of Myanmar are changing now. I hope one day I can go back to my Myanmar with rights and dignity.

Unfortunately, the current situation will impact refugee repatriation. There are still persecutions like the Myanmar authorities are forcing Rohingya to accept National Verification Cards (NVCs), which effectively identify Rohingya as ‘foreigners’ and strip them of access to full citizenship rights. Myanmar military has been torturing Rohingya to accept NVCs and restricting the movement and livelihoods of Rohingya who refused NVCs. The government’s NVC policies are an erasure of Rohingya identity.

We – the world – have not held them accountable enough. They have been allowed to carry on.”

Arcaro: Do you think sometime in the future it will be possible for all Rohingya people to live in Myanmar again with full rights and safety?

Ziaur: “Yes! Possible, if we work hard. Besides, the people of Myanmar are changing. But  I don’t see how change will happen for a very long time. I am also afraid that the military is very powerful, especially racist monks.

I don’t see how change will happen for a very long time. I am also afraid that the military is very powerful, especially racist monks.

My people are facing genocide. Those who are still inside the country can’t move from one village to another village. They are basically imprisoned in Rakhine state.”

Arcaro: Regarding your book2, what do you hope people will feel? Who is your main audience; who do you want most to read this book?

Ziaur: “The readers will know about my birth place in Myanmar, childhood experience, struggle to survive 29 years of refugee life, the country that rejects my story and my people and has never accepted us within its borders and later an activist fighting for the rights of Rohingya and justice for my people.

Already 29 years have passed since I was wrenched away from my homeland, Myanmar; for the past six years I have not seen my beloved mother. My book will expose how we suffered before reaching other countries for just saving our lives. Most Rohingya children go through grief, sadness, and despair after the loss of a parents and no future.

I believe that It will expose the Rohingya’s ongoing situation in Myanmar and also raise awareness on Rohingya refugees in neighbouring countries. And our new generation will be able to understand and imagine my clearly my fight and contribute for my community and country.

My book will be extremely important for students especially for Rohingya and everyone to inspire them how a simple a Rohingya refugee from Myanmar met Prince Charles from England and met Prime Ministers of Malaysia.”

Arcaro: How do you think your story is different from other Rohingya?

Ziaur: “To be honest, it’s not a different story but the same situation for other Rohingyas. I have written it for being a Rohingya refugee 29 years and sold seven times by human traffickers in three countries Bangladesh, Thailand and Malaysia and also ignoring the risks to speak out for Rohingya rights while being a refugee myself.”

Arcaro: How do you think the experience is for Rohingya who have been relocated to various places in the region? Can you compare life in Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Thailand etc. for displaced Rohingya

Ziaur: “Four million Rohingya population are estimated around the world from which more than 2.5 million are forced to flee and live in diaspora mainly in Bangladesh, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and some of them were trafficked to Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia and other countries around the world.

The Myanmar government made us live in the dark and grow up outside of the country. We have been living out of the country for more than two decades with little hope for positive change.

We want to go back to our homeland with safety and rights with dignity. It is very difficult to survive being a refugee. I also have knowledge that almost countries are not accepting refugees anymore.”

Arcaro: What has been your interaction with the UN or other humanitarian organizations that are dealing with the displacement from Myanmar?

Arcaro: What has been your interaction with the UN or other humanitarian organizations that are dealing with the displacement from Myanmar?

Ziaur: “I do stay in touch with humanitarian NGOs including the UN working with refugees and displaced people inside Myanmar and other countries as well. I am doing my parts while being a refugee myself to raise the voice for my community.”

Last thoughts

Ziaur -like many others- has been active posting to social media various comments on and responses to the daily anti-military coup protests in Myanmar. His voice calls out about the many and genocidal injustices that have burdened the Rohingya in the past three decades. Perhaps the pro-democracy #MilkTeaAlliance support will urge all involved that the cause of social justice means fighting for the rights of all marginalized religious and ethnic groups not only in Myanmar but in other parts of South Asia as well. Ziaur is but one voice, and his book just another public offering of a very common -and tragic- story, but many voices combined together can make change. Perhaps that is the only thing that ever has.

By Tom Arcaro

Tom Arcaro is a professor of sociology at Elon University. He has been researching and studying the humanitarian aid and development ecosystem for nearly two decades and in 2016 published 'Aid Worker Voices'. He is currently working on a second book tentatively titled "Hearing Voices: Dispatches from the margins of the humanitarian sector".